Construction of Olympia Theater in 1925

The story of the site of the edifice and construction of the theater and office building, begun in May 1925 and completed in early 1926.

When the Leach family assumed control of the Airdome Theater in June 1919, they envisioned far more for the southwest corner of Flagler Street and East Second Avenue. By the early 1920s, Flagler Street had emerged as downtown Miami’s most important commercial artery, anchoring a growing central business district defined by offices, hotels, and theaters that drew residents and visitors alike.

The 1920s proved to be not only a boom period for real estate, but also a transformative era for the entertainment industry. Although small theaters dotted downtown Miami when the Leach family first arrived in 1915, the city’s rapid growth demanded more sophisticated venues by the beginning of the third decade of the twentieth century. The construction of the Olympia Theater in 1925 would answer that demand, reshaping Miami’s theater district and signaling the city’s cultural coming of age.

Corner Owned by Edna Allen Rickmers

One of the principal figures behind the redevelopment of the Olympia Theater site was its property owner, Edna A. Rickmers. A native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she was married to a wealthy German shipbuilder when the couple relocated to Miami in 1904. Soon after their arrival, they purchased property south of Brickell Point and constructed a winter residence there. That site is now occupied by the First Presbyterian Church.

Edna Rickmers began investing in Miami real estate almost immediately. In December 1905, she acquired three lots along Twelfth Street, now Flagler Street, beginning at the southwest corner of Avenue B (today’s SE Second Avenue), for $12,000 from Emma B. Mallon. The corner lot included a residence that had previously been rented by Dr. James Jackson and his wife before they purchased land across the street to build their own home. After acquiring the property, Rickmers sold the existing house to M. J. Yarborough, who relocated it several blocks north to NE Second Avenue between Third and Fourth streets, where it became the Senate Hotel.

After land was cleared on the coveted Twelfth Street and Avenue B corner, the Hippodrome Theater was constructed and opened on October 8, 1913. The theater would remain on this corner until January 6, 1916, when the Hippodrome Theater opened in a new building across the street to the northeast corner of Twelfth Street and Avenue B (today’s Flagler Street and NE Second Avenue). Incidentally, the theater was constructed on the former site of property purchased by Dr. Jackson to build his first home in Miami.

In 1914, Edna considered selling the future site of the Olympia Theater when she signed an option for purchase contract with Ralph Worthington for $65,000. The option had a two-year term, but expired before being exercised, ensuring the control of the property remained with Rickmers, a situation which would be fortuitous for Edna and the future developers of the Olympia Theater.

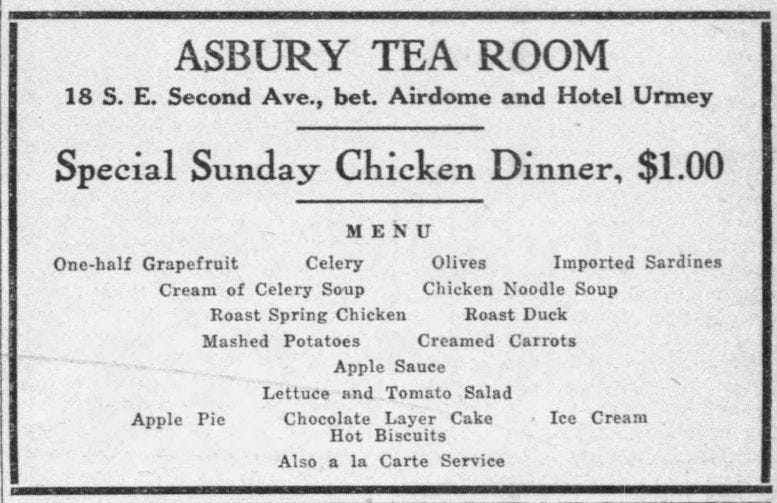

On December 15, 1916, Rickmers acquired the former Miami Club building and lot, located immediately south of her property at what would later become the Olympia Theater site. This parcel ultimately formed the precise footprint of the theater portion of the Olympia Theater and Office Building. Following Edna’s purchase, the former club was converted into a hotel and restaurant known as the Asbury Tea Room.

After the Hippodrome Theater vacated the site, the now-empty structure on Rickmers’s property was leased to theater operators Burton and Mank, who converted the show place into an open-air cinema and playhouse known as the Airdome, sometimes spelled ‘Airdrome’, Theater. The building itself was owned by Hickson & Whitmer and leased to Burton and Mank, who in turn later subleased the theater operations to a family with ambitions to shape, and ultimately control the theatrical landscape of early Miami.

A Family Enterprise

When the Leach family arrived in Miami in 1915 from Macon, Georgia, they brought with them clear ambitions to control the management of the city’s small but growing theater scene. The family had operated theaters in the small community of Macon prior to relocating to Miami. William A. Leach, the family patriarch, oversaw the financial operations, while his son Harry assumed responsibility for acquiring and managing the theaters the family leased or purchased. Harry’s brother, William D. Leach, and his sister, Mrs. Vernon Hunter, also played principal roles in the family enterprise.

The Leach family partnered with theater pioneer Stephen A. Lynch, a principal of Southern Enterprises, a company that aggressively acquired and operated theaters throughout the southeastern United States. By the mid-1910s, Southern Enterprises controlled approximately thirty theaters, a number that eventually grew to nearly two hundred. In 1923, Lynch sold his interest in the company to the Famous Players–Lasky Corporation, allowing him to shift his focus to real estate development. Among his later projects was the construction and management of the Columbus Hotel on Biscayne Boulevard in downtown Miami.

The partnership between Stephen A. Lynch and the Leach family resulted in the formation of the Paramount Amusement Company. Between 1916 and 1919, the company steadily expanded its influence in South Florida, acquiring controlling interests, through leases or management agreements, in several prominent theaters. These included the Fairfax, Hippodrome, Paramount, Fotosho, and Park theaters in downtown Miami, as well as the Community Theater in Miami Beach.

On June 1, 1920, Paramount Amusement assumed the lease of the buildings and the operation of both the theater and hotel at what was commonly known as the “Airdome corner” on Flagler Street. While Edna Rickmers retained ownership of the land, Harry Leach was tasked with integrating the Airdome into the company’s growing portfolio of managed theaters.

On Monday, June 2, the Airdome Theater reopened under new management, inaugurating its season with a vaudeville musical revue titled Martin’s Footlight Girls. Shortly after assuming the leases, Paramount Amusement purchased the existing buildings, gaining ownership of all improvements above ground on the highly desirable Airdome corner.

By the time Miami’s building boom gathered momentum, the Leach family had effectively consolidated control of the city’s theater scene. Yet their ambitions extended beyond management alone. By late spring 1924, William and Harry Leach were engaged in negotiations with both the landowner and the nation’s largest film production and distribution company, laying the groundwork for what they envisioned as Miami’s next great entertainment venue.

Miami Theater & Office Building Announced

On May 24, 1924, the Miami Daily News revealed plans for a new theater following the Leach family’s announcement of a partnership that created a new corporate entity, Paramount Enterprises. Structured as a fifty–fifty venture between the Leach family and the Famous Players–Lasky Corporation, the company designated Harry Leach as its local spokesman and on-site representative, while project financing was shared equally between the two partners.

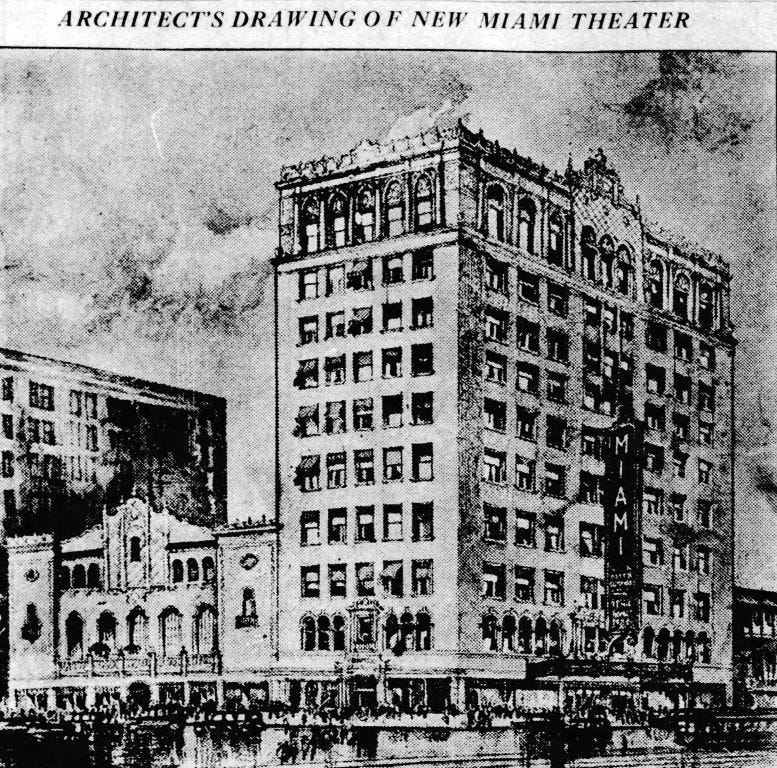

In the same article, Paramount Enterprises also announced a ninety-nine-year lease agreement with Edna Rickmers and unveiled plans to redevelop the Airdome corner into a grand complex featuring a 2,500-seat theater, office space, and a hotel. Initially projected to cost $800,000 and to be completed by January 1, 1925, the project ultimately exceeded both expectations, taking more than a year longer than planned and raising construction costs to over $1.1 million.

The building was designed to occupy a frontage of 100 feet along East Flagler Street, with a depth of 150 feet on SE Second Avenue. Although Rickmers’s property extended 165 feet in depth, a 65-foot setback was incorporated between the new theater complex and the Urmey Hotel, creating an alley separating the two structures. The design called for an ten-story office building fronting Flagler Street, with an extravagant 2,500-seat theater located at the rear of the site and accessed from SE Second Avenue. Altogether, the building’s footprint encompassed approximately 21,500 square feet.

According to the Miami News, the land agreement was structured as a graduated lease, with a maximum annual rental of $50,000. The article also noted that “Mrs. Rickmers recently refused an offer of $750,000 for the purchase of the ground.”

The project was initially referred to as the Miami Theater and Office Building, a provisional name that served as a descriptive placeholder rather than a permanent title. As construction progressed, the principals of the Famous Players-Lasky would look to a familiar figure for inspiration when selecting the building’s final name.

Paramount Enterprises commissioned a designer with whom Famous Players–Lasky had collaborated on several previous projects. Following the formation of the partnership and the public announcement of the development, architect John Eberson began work on the design, employing the innovative style known as the atmospheric theater.

Architect John Eberson

John Eberson (1875–1954) was one of the most influential theater architects of the early twentieth century and is best remembered as the creator of the “atmospheric theater.” Trained as an architect in Europe and later working in the United States, Eberson began his career designing conventional vaudeville and movie houses before revolutionizing theater architecture in the late 1910s and early 1920s. His atmospheric concept transformed theater interiors into immersive environments meant to evoke outdoor settings, Mediterranean courtyards, Italian gardens, or Spanish plazas, complete with simulated night skies, twinkling stars, and architectural façades. This approach fundamentally changed how audiences experienced motion pictures, shifting theaters from utilitarian entertainment halls into destinations of fantasy and escape.

Between 1912 and 1924, Eberson emerged as the preferred architect for major theater chains, including those associated with Famous Players–Lasky and Paramount interests. His work during this period laid the foundation for the golden age of movie palace design in the 1920s. While his later projects would become even more elaborate, Eberson’s early theaters already demonstrated his mastery of spatial drama, illusion, and audience experience, qualities that made him a natural choice for ambitious projects like the theater Paramount Enterprises envisioned for downtown Miami.

John Eberson was no stranger to Miami when he was hired by Paramount. In an article published in the Miami Daily New on July 26, 1925, his architectural philosophy was revealed:

“I have been coming to Miami for a number of years, so that the city is not new to me except that it has become practically unrecognizable through its remarkable growth. To me, the most striking examples of beauty and architectural perfection are the Venetian casino at Coral Gables and the News Tower. I have had training which has instilled in me a feeling enabling me to appreciate color deeply. I disagree with so many artists who claim that real art is simplicity. I credit nature with most of the art to be found in this world. The natural beauty of Miami’s colorful sky and the tropical flora found here make a wonderful setting and should create an appreciation of a style of architecture originated and at home in southern Spain.”

His appreciation for the natural beauty of South Florida was reflected in his approach to designing the Miami Theater. Drawing on his architectural training, recent work, and the prevailing stylistic themes of the Magic City’s building boom, Eberson produced a design that is widely regarded as one of the finest achievements of his career.