Miami and the Spanish American War – Part 1 of 3

Part one of a three-part series on Camp Miami during the Spanish American War in 1898. Camp Miami was a training center established in the two-year old city of Miami in the summer of 1898.

Miami was less than two years of age when, in April 1898, the United States went to war with the aging empire of Spain over the issue of Cuban independence. A picturesque island with a lively, cosmopolitan capital in Havana, Cuba had represented, since its establishment in the 16th century, one of Spain’s most important New World possessions.

However, the fitful colony had been in a state of rebellion with Spain for several decades as the end of the century approached. In the years immediately prior to the Spanish-American War, Spain and Cuba were engaged in a savage guerrilla war. A series of events and controversies, pitting Spain and the United States on opposite sides, exacerbated by an inflammatory American press, placed the two nations on a collision course that ultimately led to war.

The “Splendid Little War,” as John Hay, the American Secretary of State, characterized it, lasted but three months, resulting in a decisive victory for the United States over an opponent whose fortunes had declined precipitously since it had amassed an empire in the New World three centuries earlier. The war represented a watershed in American foreign policy. Along with the ensuring peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, the conflict marked the emergence of the U.S.by then the world’s foremost industrial nation, as an imperial power with possessions and influence that now extended across the globe.

At the time of the war, Miami contained 1,200 residents who lived in today’s downtown neighborhood. Miamians experienced the war in different ways. Even before the outbreak of hostilities on April 24, the city’s residents witnessed the arrival of large numbers of persons fleeing Key West due to its proximity to Cuba and the theater of war. Additionally, many Miamians feared that the Spanish navy would invade their municipality as part of an offensive against several coastal Florida cities.

The Miami Metropolis, the city’s lone newspaper, fanned this fear, a totally unfounded concern, averring that Spanish warships would destroy Henry Flagler’s posh Royal Palm Hotel or another city landmark. This fear prompted a demand for coastal defenses. Consequently, the U.S. Army erected an earthen mound forty-five feet in diameter and twenty feet in height on a ridge overlooking Biscayne Bay near today’s Brickell Avenue and Eighteenth Road. There they installed two heavy guns. Although it was formally known as Fort Robert W. Davis, for a member of Florida’s delegation in the United States House of Representatives, most Miami residents referred to it as Fort Brickell. However, the fort remained unfinished for the duration of the brief conflict. In the meantime, to allay concern over an invasion, 300 locals organized a volunteer home guard unit, the Miami Minutemen, who drilled with arms on the grounds of the Royal Palm Hotel.

At the time of the conflict, the United States military, woefully unprepared for fighting, sought bases on the Florida peninsula from which an invading army could reach the nearby island. The Army examined several sites in Florida for camps, but it rejected Miami, despite the efforts of Flagler, who saw the presence of an Army camp in the Magic City the opportunity to enhance the business of his Florida East Coast (FEC) Railway through the transport of vast quantities of freight and soldiers.

Despite this rejection, the FEC Railway interests began preparing a soldiers’ camp north of downtown in the piney woods. Under intense lobbying from the influential Flagler, the Army decided to take a second look at Miami for the site of a training camp. In a letter to Senator Thomas Platt, Flagler was effusive—and dissembling—in his praise of the young community, proclaiming that its summers were extremely pleasant. Flagler also rhapsodized over the city’s inexhaustible supply of the purest of water and the presence of a constant sea breeze for the comfort of the offices and the enlistees.

This second look at Miami by the Army as a possible campsite again resulted in a rejection. Undaunted, Flagler redoubled his efforts to bring an Army camp to Miami, and ultimately prevailed when Major General Nelson Miles wrote Secretary of War Russell Alger, urging him to send 5,000 troops to Miami, which he described as “a perfect camp site with the ground already cleared and health conditions that would enable the troops to be protected from any disease.” Miami had at last gained its coveted campsite, taking its place alongside Tampa, Lakeland, Jacksonville, and Fernandina, which also hosted soldiers’ camps.

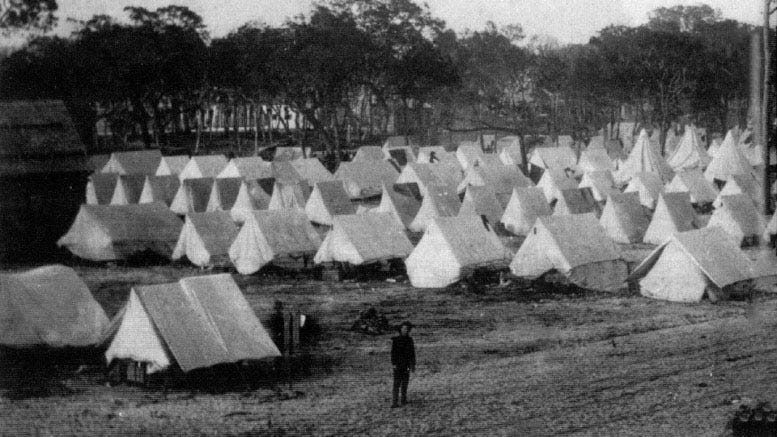

The first soldiers arrived in Miami on June 24, 1898. Two weeks later, more than 7,000 volunteers from Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas had established camp in an area covering a wide rectangular swath of the northern sector of today’s downtown. The facility stretched in an east-west direction from today’s Biscayne Boulevard to Northwest Second Avenue. In the north, the camp abutted the picturesque FEC Railway station on the western portion of today’s Miami News/Freedom Tower site. Its southern border was Northeast Second Street.

In the next of this three-part series, we will examine Camp Miami, its impact on its residents as well as on its host city, whose population at the time was little more than 1,200.

Related Articles:

Images:

Cover: Tents in Miami for Soldiers in 1898. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 1: Sinking of the Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898.

Figure 2: Remnants of Fort Brickell in 1900.

Figure 3: Cartoon of Spanish American War.