Olympia Theater Grand Opening in 1926

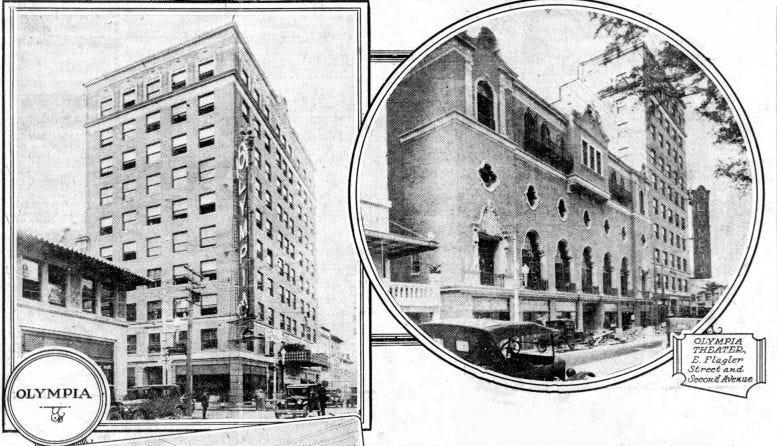

Miami's grand theater of the 1920s is celebrating its centennial. The theater and office building at 174 E Flagler Street, opened on Thursday evening, February 18, 1926.

As the Olympia Building began welcoming its first office tenants in December 1925, work on the adjoining theater was behind schedule. The principals of Paramount Enterprises had envisioned a single grand opening for both the commercial tower and the theater, but unforeseen delays forced them to abandon that plan.

While businesses settled into their new offices, architect John Eberson supervised the intricate final phases of the auditorium and stage construction. By late January 1926, the theater’s interior and mezzanine were nearing completion. Yet one critical exterior element remained unfinished, preventing the Paramount team from announcing an official opening date. This is the story of the grand opening of the Olympia Theater and Office building on Thursday, February 18, 1926.

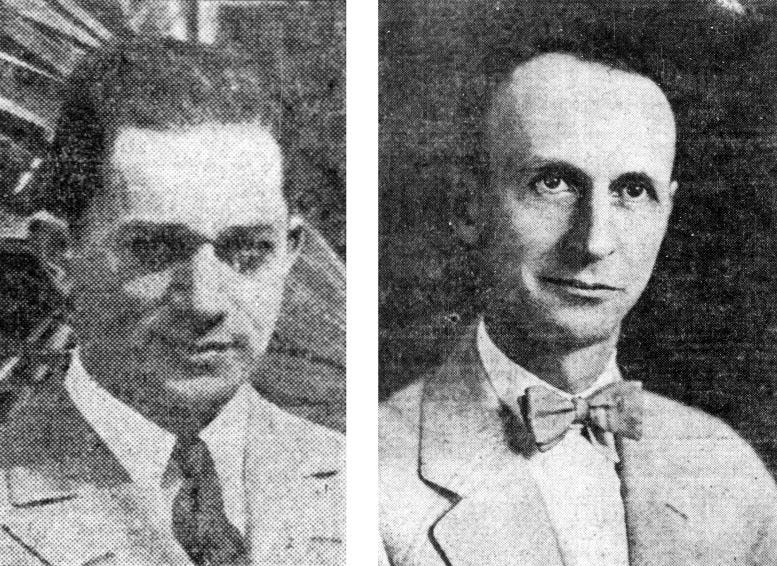

Theater’s Orchestra Conductor

As construction of the Olympia Theater neared completion in January 1926, the principals of Paramount Enterprises turned their attention to assembling the team that would operate the new venue. Harry Leach, general manager of the partnership between his family and the Famous Players-Lasky organization that built the theater, faced the task of recruiting stagehands, ushers, parlor attendants, concession workers, and, importantly, a conductor to lead the theater’s orchestra.

The Olympia was opening during the height of the silent film era, when motion pictures relied on live musical accompaniment rather than recorded dialogue. ‘Talkies’ would not arrive until October 1927 with the release of “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson. To heighten drama and provide a musical score, major metropolitan theaters like the Olympia featured full orchestras, while smaller regional houses often relied on a single organist to achieve a similar effect.

For this critical role, Paramount selected a familiar and seasoned conductor, E. Manuel Baer, to direct the 25-piece Olympia Theater Orchestra. Baer brought eight years of experience with Famous Players-Lasky, having conducted at New York City’s Rialto Theatre and Rivoli Theatre. He relocated to Miami in January 1926, quickly settling in and organizing auditions for instrumentalists and vocalists. While the finishing touches were being applied to the auditorium, stage, and orchestra pit, Baer conducted screen tests on the second floor of the adjoining office building.

Baer was very fond of Miami based on a couple of earlier trips to the Magic City prior to accepting the job with the Olympia. He embraced not only the opportunity to lead the Olympia’s orchestra but also the prospect of establishing a conservatory to train aspiring local musicians. During auditions, he made a concerted effort to recruit as many Miami-based performers as possible.

As work on the building continued, Baer finalized his orchestra and began rehearsals for opening night. By early February, management announced that the debut would be postponed until the third week of the month due to delays involving exterior signage deemed essential for the grand unveiling. Though the precise program for the evening had yet to be announced, the orchestra stood ready to make the occasion unforgettable.

Opening Night Announced

On February 6, 1926, the leadership of Paramount Enterprises, a partnership between the Leach family and the Famous Players-Lasky organization, arrived in Miami to finalize plans for the long-awaited debut of the Olympia Theater. The executives traveled by steamship H.F. Alexander from New York and, upon their arrival, announced that opening night would take place on Thursday, February 18, 1926.

Among those in the delegation were Adolf Zukor, president of Famous Players-Lasky; Jesse L. Lasky; and Samuel Katz of Balaban & Katz, which had merged with Famous Players-Lasky to form the Publix Theatres Corporation. After meeting with Harry Leach to review the theater’s progress, the group agreed that the building and its operations would be ready in time for the 18th and made the formal announcement. Following their meeting, Zukor, Lasky, and Katz continued to Palm Beach, returning a week later to stay at the newly opened Miami-Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables in advance of the grand opening.

Traveling with the party was Thomas Meighan, one of the era’s most prominent silent film stars and a contract player with Famous Players-Lasky. Meighan traveled with the group to Miami to film scenes for a new movie called ‘Palm Beach Girl.’ While the executives vacationed in Palm Beach, he remained behind to complete shooting before attending the Olympia’s opening festivities. During his stay, he and his wife lodged at the Flamingo Hotel.

Before departing for Palm Beach, Zukor recommended that the Olympia’s inaugural feature be “The Grand Duchess and the Waiter,” starring Adolphe Menjou. Freshly released to theaters on February 8, 1926, the film offered an opportunity to pair the company’s latest production with the unveiling of what executives considered their crown jewel theater. Expressing confidence in the new venue, Zukor remarked to Leach, “I am sure the new theater will be a success. It is one of the most beautiful I have ever seen, both inside and out.”

Training the Staff

A few days after the arrival of the company’s top executives, Harry Marx, director of theater management for the newly formed Publix Theatres Corporation, reached Miami on February 10 to assist with preparations for opening night at the Olympia Theater. Publix had been established following the merger of Famous Players-Lasky and Balaban & Katz, the Chicago-based theater giant, and was tasked with managing the theaters owned by the combined enterprise. Recognized as an authority on large-scale theater operations, Marx was dispatched to support Harry Leach in organizing both the debut and the long-term management of the new venue.

Working together, Marx and Leach created a formal training program for the Olympia’s personnel department. The curriculum emphasized discipline, attentiveness, and even elements of military drill. Employees were instructed in the principles of courtesy, tolerance, and enthusiasm, values expected to define the theater’s culture regardless of one’s position. For Publix, careful preparation and professional standards were central to both opening night and ongoing success.

The pair oversaw the hiring and training of the full theater staff, including ushers, parlor attendants, and concession workers. All ushers were men and required to wear uniforms while on duty. In keeping with Publix policy, accepting tips was strictly forbidden, reinforcing the organization’s commitment to professionalism and consistent service.

Signage Installed

In early February, the long-anticipated components for the exterior sign of the Olympia Theater finally arrived. Because of its extraordinary scale, the contractor charged with its installation had to carefully engineer how it would be secured to the structure. Weighing nearly two tons, the copper sign required anchoring directly into the building’s foundation to support its immense mass. Though monumental in size, it was thoughtfully designed so that its architectural lines complemented the detailing of the theater itself.

For nearly two weeks, curious onlookers lined Flagler Street to watch the installation unfold. When the work was completed on Wednesday, February 11, the city issued the permit for the towering electric display, 55 feet high and 10 feet wide, confirming that the theater’s exterior would be ready for its much-anticipated grand opening.

The sign was said to be the largest theater advertisement in Florida and the largest hanging sign in the South. Composed of 3,500 electric bulbs, it spelled out “Olympia” within a dynamic border of moving lights. Above the “O,” a heraldic crest rendered in colored illumination added a dramatic touch. The brilliant display served as a fittingly grand accessory to a building designed to house one of the region’s most lavish theaters.

Once the sign was secured at the corner of Flagler Street and Southeast Second Avenue, a bronze tablet was installed near the Flagler Street entrance to commemorate the theater’s completion. The plaque bore a simple dedication inscription:

“Olympia Theater, Dedicated to the Lovers of Art, Music and Wholesome Entertainment.”

Early Impressions & Finishing Touches

On Saturday, February 13, just four days before the scheduled grand opening, reporters were given access to tour and witness the final preparation details for the theater’s debut. A writer for the Miami Herald described the interior of the auditorium in glowing terms.

“The interior of the theater, which represents a startling departure from the accepted style in theater decoration, has been built to give the illusion to the spectators that they are sitting in a large Italian garden, closed in on three sides by the walls of an imposing castle or villa. On the fourth side is laid a Spanish scene focusing on a rectangular gateway through which the screen and stage proper can be seen. That the illusion should be perfect, the walls of the villa have been built out from the walls of the theater to give a three-dimensional appearance. Quaintly tiled eaves, grilled turrets glowing with dim colored lights, and Italian style roof lights shining in old gold are outstanding details of the scene.

Overhead an almost exact duplication of a Florida sky at night has been produced. There is the illimitable deep blue which Miamians know so well, twinkling stars, a moon moving slowly across the firmament and drifting billows of cloud. The entire ceiling of the theater has been modeled to represent this sky effect. It is the device of John Eberson, architect of the theater, who personally supervised the construction and decoration of the building.

The boxes have been built to resemble the balconies of the castle and are roofed with pillared canopies of a delicately carved design. At the rear of the balcony, arched French doors resemble the upper windows of the castle. Looking from the stage, the balcony is seen to be covered over with a huge arched pergola, hung with swinging lanterns of red, amber, green and yellow shades. An elaborate lighting installation permits the theater and stage to be tinted in white, amber, blue, red and green.”

On Sunday, February 14, contractors working in concert with architect John Eberson labored intensely to complete the final details inside the auditorium of the Olympia Theater. The pace did not slow as opening night approached as crews continued their work through the eve of the debut to ensure that every ornament, fixture, and finish were perfect and alignment with Eberson’s vision.

Meanwhile, in the orchestra pit, E. Manuel Baer and his musicians rehearsed in preparation for the long-anticipated premiere. As carpenters and craftsmen made last-minute adjustments overhead, the strains of the orchestra echoed through the nearly completed hall during a series of final dress rehearsals.

Ticket Sales

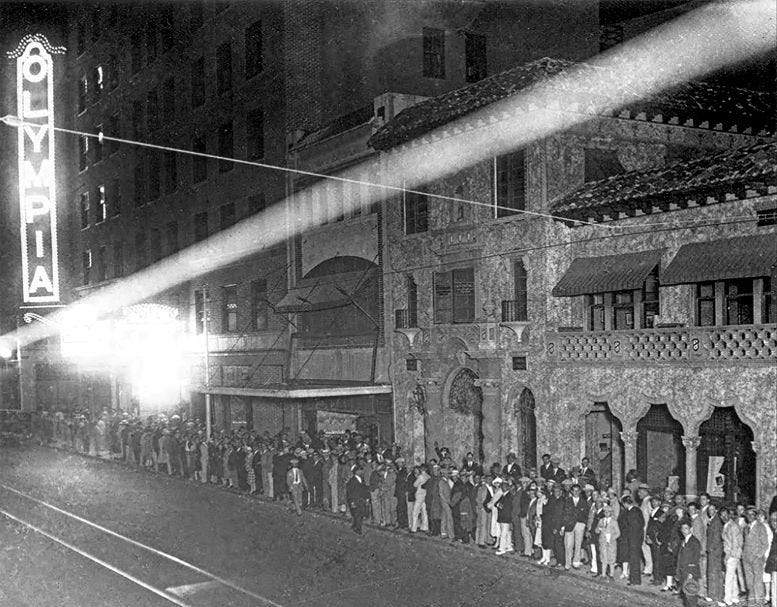

Although blocks of seats were reserved for company executives, invited guests, and local dignitaries, ample tickets remained available to the public for the debut of the Olympia Theater. Sales opened on Monday, February 15, and by day’s end, half of the available seats had already been claimed. Beyond the excitement of opening night itself, many were excited to attend performances of conductor John Whiteman and famous opera sopranist Vera Lavrova.

By Monday evening, theater officials reported that seats in the rear rows were selling just as briskly as those in the front of the house, offering patrons the opportunity to choose their preferred section assuming they acted quickly. Management also emphasized that all seating for the event was reserved, underscoring the urgency to secure seats for the event.

Within two days of tickets going on sale, the performance was completely sold out. Even so, many who were unable to secure seats, or could not afford them, gathered outside the theater, hoping to catch a glimpse of the evening’s celebrities as they arrived and departed from the much-anticipated premiere.

Special Guests

The grand opening of the Olympia Theater was more than a milestone for Paramount Enterprises and its affiliated companies, it was a bold declaration and validation of Miami’s tremendous growth during the 1920s. Representing the ownership group were members of the Leach family, alongside industry titans including Adolf Zukor, president of Famous Players-Lasky; Jesse L. Lasky; and Samuel Katz, head of Balaban & Katz. Their presence underscored the importance of Miami’s grand theater to the enterprise that would eventually become Paramount Pictures.

Those responsible for bringing the theater to life were also honored. Architect John Eberson, assistant architect R.E. Hall, and general contractor George A. Fuller were recognized for delivering a structure of remarkable scale and elegance. Edna Rickmers, owner of the land beneath the theater and credited with naming the building, occupied a private box alongside the Leach family and distinguished guests including Grace Graham Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt III, and others.

Miami’s civic leadership was equally well represented. Mayor E. C. Romfh attended with his wife and delivered the opening remarks during the dedication ceremony. Prominent pioneer families and community leaders filled the audience, among them members of the Reilly, Merrick, Urmy, Roney, Wharton, Tatum, and Sewell families. Also in attendance was John McEntee Bowman, partner of George Merrick in the development of the Miami-Biltmore Hotel.

National theatrical figures further elevated the evening’s prestige. Most notable was Florenz Ziegfeld, famed producer of the Ziegfeld Follies, who attended with his wife, famous actress Billie Burke. They were joined by Gene Buck and his wife, representing the creative leadership behind the celebrated Ziegfeld revue. Their presence signaled that the Olympia’s opening was not merely a local celebration, but an event of national theatrical importance.

Grand Opening Evening

On the evening of Thursday, February 18, 1926, months of preparation culminated in the long-awaited opening of the Olympia Theater. Harry Leach had promised Miami patrons a new standard of service, and his staff of fifty, rigorously trained in the weeks leading up to the event, stood ready to deliver on that pledge.

Automobiles pulled to the curb along Flagler Street, where uniformed footmen greeted arriving guests and escorted them into the lobby. The sidewalk was lined with elegantly dressed theatergoers, orderly and patient as they awaited their turn to enter. For those holding tickets, the anticipation was unmistakable; excitement filled the seasonal February air.

Inside, operations ran with precision. Three seasoned attendants managed the ticket office, while experienced doormen collected admissions at the entrance. Directors, floor captains, a chief usher, and an assistant supervisor coordinated a corps of uniformed ushers. Porters, maids, and page boys were stationed throughout the building to assist guests. Amenities included a parcel checkroom and a dedicated lost-and-found department.

Every element of the theater was designed with comfort in mind. Cushioned leather seats, thick carpeting, softly shaded lighting, and conveniently placed exits enhanced the experience. Furnished box seats offered an added touch of exclusivity, and by curtain time, the full capacity of 2,500 seats had been filled, marking a triumphant beginning for the Olympia.

As the audience settled into their seats and anticipation built inside the auditorium, the curtain rose for the first time to reveal the picturesque stage. From either side, two trumpeters dressed in Spanish costume stepped forward, their ceremonial bugle calls signaling the formal commencement of the evening’s festivities.

Their fanfare gave way to the opening overture, conducted by E. Manuel Baer. The orchestra began with “The Star-Spangled Banner,” prompting the entire audience to rise in tribute, both to the nation and to the artistry of the musicians assembled in the pit.

Serving as master of ceremonies was Harry Marx, director of theaters for the Publix Theatres Corporation. He first introduced Miami Mayor E. C. Romfh, who delivered the dedicatory address. The mayor commended the principals of Paramount Enterprises, along with the architect and builder, for their achievement. Reflecting on Miami’s rapid rise, he declared that the opening of the Olympia was “one of the most splendid answers to adverse publicity in the North,” a pointed reference to newspaper warnings cautioning against the speculative fervor surrounding the city’s dramatic growth.

Following the mayor’s remarks, Baer returned to the podium to lead the evening’s principal musical selection: 1812 Overture by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The powerful work, depicting Napoleon’s advance on Moscow and his eventual retreat, was enhanced by dramatic lighting effects that heightened its entertainment value. The performance was met with resounding applause setting an exultant tone for the remainder of the celebration.

The evening’s spotlight then turned to opera singer Vera Lavrova, also known as Baroness Royce-Garrett, a celebrated coloratura soprano who quickly captivated the audience. She began with “Song of India” from Sadko by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, earning enthusiastic applause. For her first encore, she performed the waltz scene from Roméo et Juliette by Charles Gounod. She concluded with the sentimental favorite “When You and I Were Seventeen,” a selection warmly received by the crowd and a fitting finale to her triumphant appearance.

The musical crescendo of the night came with the arrival of guest conductor Paul Whiteman. Having performed earlier that evening in Coral Gables, Whiteman traveled to the Olympia to present a sweeping cross-section of his repertoire. His program ranged from selections inspired by grand opera to the jazz and dance numbers that had made him one of the most recognizable and popular musical figures of the era.

Following the festivities at the Olympia, many of the city’s most prominent guests made their way a few blocks east to 36 Biscayne Boulevard for the grand opening of Stephen Lynch’s Columbus Hotel. Lynch maintained a longstanding relationship with the Leach family, and his Southern Enterprises theater chain worked closely with Famous Players-Lasky, suggesting that the decision to debut the hotel on the same evening as the Olympia Theater may have been more than mere coincidence.

Recognizing that many Olympia attendees also planned to celebrate at the Columbus, organizers scheduled a late dinner seating in the roof garden of the hotel’s seventeenth-floor to accommodate guests attending both occasions. Entertainment for the evening featured Earl Burtnett’s orchestra from the Los Angeles Biltmore, marking the ensemble’s first performance in Miami. Not surprisingly, the guest lists for the two grand openings overlapped considerably.

Epilogue

On Friday, February 19, the Olympia Theater transitioned from opening-night celebration to its regular operating schedule. Doors opened each day at 11 a.m., with morning admission, valid until 1 p.m., priced at 25 cents for children and 50 cents for adults. For afternoon and evening screenings, running from 1 p.m. to 11 p.m., tickets increased to 50 cents for children and 85 cents for adults. The theater’s first featured silent film, “The Grand Duchess and the Waiter,” headlined the program during its initial two days of official operation, marking the beginning of a new era of entertainment in downtown Miami.

Over the decades, the Olympia has experienced periods of prosperity and decline, yet it has remained anchored on the same downtown corner for more than a century. Recently, the City of Miami sold the building and its auditorium to SLAM! Charter School, which plans to preserve the historic structure while incorporating it into its educational programming. After 100 years serving as a theater, concert hall, and office building, E. Manuel Baer’s original vision of a conservatory for musicians may find renewed expression through the school’s arts-focused curriculum, which integrates music education into its arts management program.

Resources:

Miami Herald: “Talent Will Be Aided”, January 20, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Orchestra Projected”, January 27, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Theater Opening Delayed”, February 5, 1926

Miami Herald: “Theater Owners Arrive”, February 7, 1926

Miami Herald: “Director Will Assist”, February 10, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Theater Expert“, February 11, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Theater Program Set“, February 11, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Decoration Elaborate“, February 12, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Big Olympia Sign Hung“, February 12, 1926.

Miami Tribune: “New Theater To Present Scene of Rare Beauty“, February 13, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Theater To Be Opened“, February 14, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Tickets Sell Rapidly“, February 16, 1926.

Miami Tribune: “Olympia Opening and Columbus Initial Dinner Today”, February 18, 1926.

Illustrated Daily Tab: “Olympia Theater Dream Come True”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Olympia Theater Open”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Olympia Opens Today”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Olympia To Be Gay with Society Throng”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Tribune: “Opening of Olympia Theater Fulfills Miami Managers Dream”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Tribune: “Beauty of Old Spain Seen in Olympia Theater”, February 18, 1926.

Miami Tribune: “Throng Attends Gala Opening of New Theater”, February 19, 1926.

Thank You Casey! I never realized that the Olympia and the Columbus Hotel opened at the same time. Here's hoping the Olympia will continue to be a precious and preserved theater for the public in South Florida.

For anyone who hasn't seen the theatre, it's truly a stunning gem. I remember being enchanted when I first went there in 1988 for a film festival screening. A treasure.