Original & Infamous North Miami

Once referred to as the red-light district, the northern suburb of Miami incorporated as the City of North Miami in 1912. It was a short lived municipality that was annexed into Miami in June 1913.

As the City of North Miami, situated between NE 119th Street and NE 163rd Street, prepares for its centennial celebration in February 2026, it’s worth asking: what’s in a name? The municipality was originally incorporated as the Town of Miami Shores, but in July 1931 the Florida Legislature required a name change to North Miami. With another municipality called Miami Shores located just a mile to the south, lawmakers stepped in to eliminate the mounting confusion.

Reflecting on the name “North Miami,” this avocational historian can’t help but recall its significance during the Magic City’s formative years. Few realize that “North Miami” first referred simply to the rough-and-tumble saloon district just beyond the city limits, and later to a short-lived municipal incorporation known as the City of North Miami in 1912. What follows is the story of how that name evolved.

North Miami Saloon District (1896 – 1908)

When Henry Flagler’s team negotiated with Julia Tuttle and Mary Brickell over the land concessions granted to the Florida East Coast Railway, an incentive for Flagler to extend his line and construct a grand hotel, one of the most significant terms was that the new city be established as a dry municipality. Every deed filed afterward carried a clause prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcohol on any structure built upon the conveyed property. Flagler’s representatives did, however, secure an exemption for the firm’s Royal Palm Hotel, allowing alcohol to be sold and served there.

Because Miami was founded as a dry city, the area immediately north of its original limits naturally developed into a saloon district. Though lacking an official designation, it became known informally as ‘North Miami’ simply because of its position relative to the city. This enclave offered the very indulgences that were forbidden within Miami’s borders, except, of course, for guests of Flagler’s Royal Palm Hotel.

The area known as North Miami emerged during Miami’s incorporation year and gradually shifted from a simple place to buy a drink into a district where a full range of vices flourished. New establishments, often described euphemistically as “resorts”, offered alcohol, gambling, and prostitution to anyone willing to venture into the area.

As North Miami evolved, it became widely recognized as the city’s red-light district. It was centered just beyond the point where Avenue D ended at Miami’s northern boundary. Using today’s street grid, the core of this enclave of vice sat at the northeast corner of North Miami Avenue and NE 11th Street, the present-day location of the nightclub Eleven.

Beyond the objections of residents who decried the district’s immoral activity, members of both local and national temperance movements campaigned to shut down North Miami. In March 1908, noted crusader Carrie Nation was invited to the Magic City by Bobo Dean, the Miami Metropolis editor, and Ida Nelson, a leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), to bolster the effort.

Nation spent a week in the city, addressing large crowds from a tent erected across Flagler Street from the Dade County Courthouse. There, she castigated “do-nothing” county officials for failing to confront the situation in North Miami often calling out political leaders and officers by name if they dared to attend. Each evening, she visited one of the district’s “resorts,” publicly shaming patrons and smashing bottles behind the bar with her umbrella.

By the summer of 1908, crime in North Miami had reached a breaking point, and Miami residents had grown weary of the relentless headlines spilling out of the district. Robberies, brawls, and even murders had become weekly events. Although the City of Miami lacked the authority to shut the area down, North Miami fell under the jurisdiction of Dade County, whose officials did have the power to act.

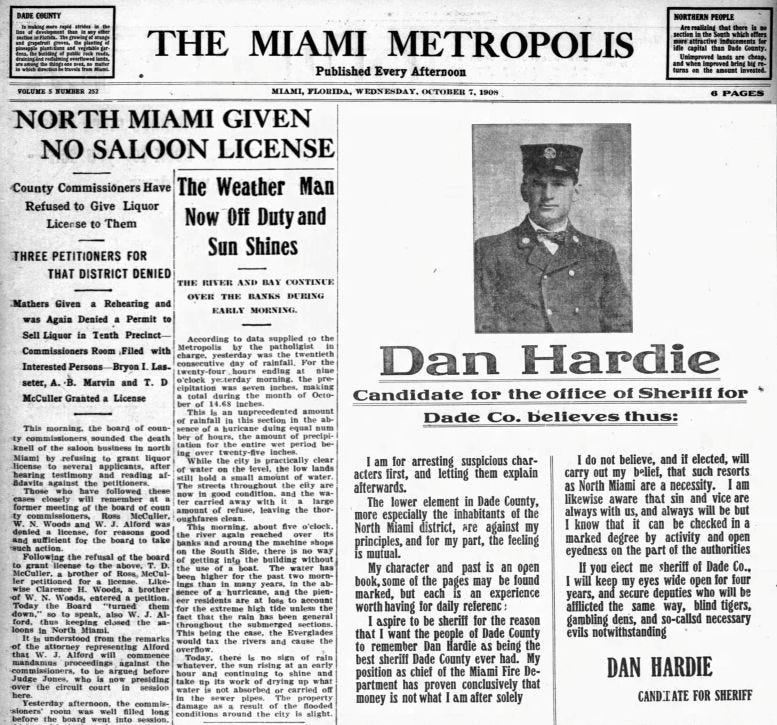

Dan Hardie, Miami’s first fire chief and a man known for his upright character, ran for Dade County Sheriff on a platform centered on eliminating North Miami. Beginning in October 1908, the County Commission began refusing all new liquor licenses and declined to renew existing ones. When Hardie won the sheriff’s race, it signaled the end of the North Miami red-light district. Upon taking office, he set about clearing the area of saloons, “resorts,” and every other form of vice that had taken root there.

Although the district was dismantled in its original location, where it had operated from 1896 to 1908, it soon resurfaced on the northwest edge of Overtown. There, it adopted the sardonic nickname “Hardieville,” mocking the sheriff who had driven it out. The address changed, but the behavior, vice, and crime continued much the same.

Annexation Overture in 1911

In the years following the cleanup of the old red-light district, landowners wasted no time carving the area into small subdivisions which were considered early northern suburbs of the Magic City. As new homes went up and the once-isolated stretch of unincorporated Dade County filled with new residents, the community north of Miami’s original boundary began to imagine a different future for itself. By 1911, the residents had gathered to discuss whether it was time to join their ambitious neighbor to the south.

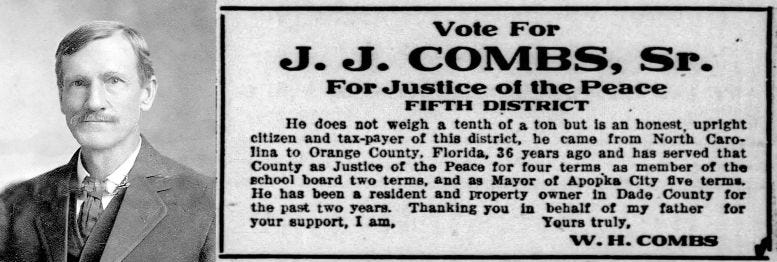

That conversation came to a head on the evening of December 1, 1911, when the people of what was still commonly called North Miami assembled at the Biscayne Drive home of Theodore G. Houser which was located at today’s 1604 NE Second Avenue. The purpose was to decide what conditions they would set before agreeing to become part of the City of Miami. Houser was chosen to chair the committee charged with defending the community’s interests, while Jesse Jay Combs, father of pioneer funeral director Walter Combs, was selected as secretary, responsible for outlining the formal steps toward annexation.

Among those gathered that evening was Mr. Gates, a recent transplant from Los Angeles who had invested considerably in Buena Vista real estate. Drawing on his experience in California, he explained that newly annexed districts there were often granted a three-year exemption from property taxes, an incentive he believed could benefit North Miami as well. A strong advocate for joining the City of Miami, Gates spoke passionately for nearly an hour, laying out a detailed case for why annexation made sound economic sense.

By the time the discussion ended, the room had shifted decisively in favor of the idea to becoming a part of the City of Miami. As recorded in the meeting’s minutes, the assembled residents reached the following conclusion:

“Resolved: That it is the sense of this meeting that we come into the city, provided that the City of Miami will exempt us from city taxes for three years, such action to be spread upon the minutes of the city council, and placed upon the ballots to be cast at said election; also to give us fire protection as soon as possible.”

When Houser and Combs presented the proposed annexation terms to the Miami City Council, the tax-exemption provision quickly met resistance. Council members were unwilling to support it, and the clause was ultimately removed. Without that incentive, the so-called Greater Miami Proposition became far less appealing to residents of the northern suburb. When the ballots were cast in Houser’s barn, which was the makeshift polling place at 1604 NE Second Avenue (today’s address), on March 12, 1912, voters in North Miami rejected the proposal by a wide margin, and the annexation effort was decisively defeated.

With Miami boxed in to the east by Biscayne Bay, the young city could grow only to the south, west, or north, making annexation its most practical path to expansion. The question would return soon enough, surfacing again in 1913 as Miami continued to look for room to stretch its boundaries.

Broadmoor & Edgewater Subdivision in 1911

Unincorporated North Miami received a significant boost in late 1911 when Frederick Rand, who would later construct the Huntington Building at 168 SE First Street and envision transforming East Second Avenue into Miami’s own version of New York’s Fifth Avenue, turned his attention to the area. On December 15, 1911, Rand and his partners, M. P. Freeman and Gladys Hoag, registered two new development companies with the State of Florida. Their goal was to create the subdivisions of Broadmoor and Edgewater which were carefully planned communities aimed at affluent Miamians and well-to-do newcomers from the North who wanted homesites overlooking the scenic expanse of Biscayne Bay.

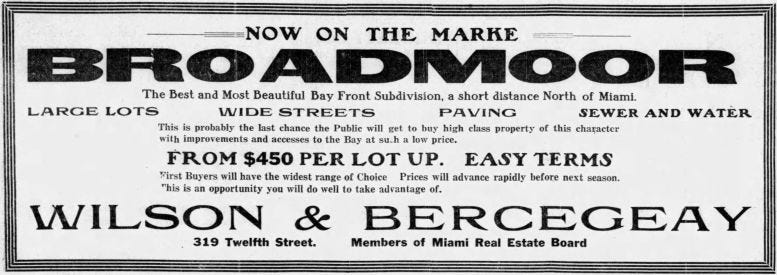

The Broadmoor subdivision was located just south of the Buena Vista neighborhood bounded by today’s NE 34th to NE 36th Street, east of Biscayne Boulevard. It advertised as having large lots, wide streets, sewer and water for $450 and up. While Broadmoor was financed and developed by Rand and his partners, the Walter Waldin Investment Company acquired the sole agency to market and sell the lots in this subdivision.

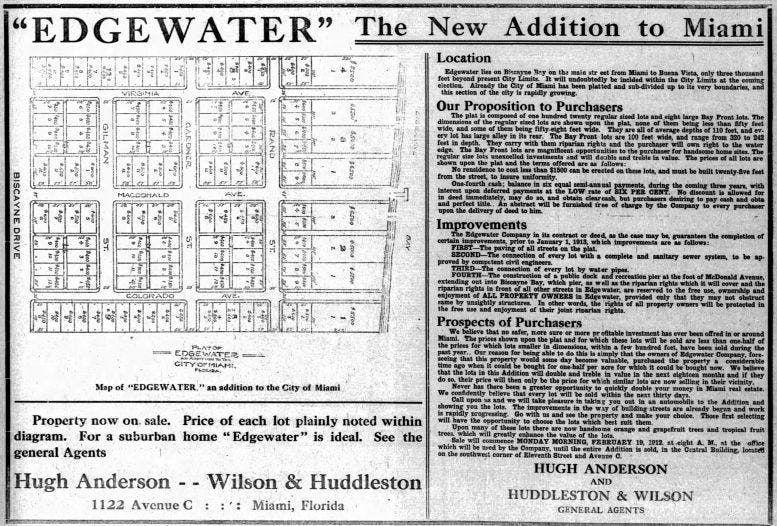

The Edgewater subdivision was located closer to the Miami city limits and bounded by today’s NE 22nd to NE 24th streets. Years later, the name Edgewater was expanded to describe a neighborhood which includes an area encompassing multiple subdivisions from Miramar to Broadmoor, or from NE 17th to NE 37th Streets along the Biscayne Boulevard corridor.

A journalist for the Miami Daily Metropolis described the merits of the new subdivision in an article published on February 19, 1912, writing “Edgewater – picture it on your visiting cards, or, better still, picture it the setting of that Miami home, that you have always longed for, near the bay, free from the annoyances of the business section of the city and yet less than two-thirds of a mile distant from the corporate line.”

The article went on to state: “Edgewater is the name given to a beautiful tract of land just north of Miami on the bay shore with the prices for lots well within the reach of any one able to own his own home. Each lot will have a complete sanitary service, will be piped for water and will have frontage on avenues delightfully wide and excellently paved.”

That final line underscored an important reality for developers operating in unincorporated Dade County at the time. Because the area lay outside any municipal authority, the responsibility for building and maintaining roads, utilities, and other infrastructure fell entirely on the subdivision’s developers. As new neighborhoods continued to take shape in the growing suburb north of Miami, the lack of formal governance became increasingly apparent and so did the need for a more organized structure to manage the expanding community.

Miramar Subdivision in 1912

By the summer of 1912, Rand and his circle of investors secured a parcel of marshland just beyond Miami’s northern boundary, acreage the Miami Herald dismissed as “all but worthless except for the position it occupied with reference to riparian rights.” Yet its location was strategic in that the tract sat just north of the future entrance to Collins Bridge, then under construction and soon linking Miami with the fledgling community across the bay.

To transform the soggy terrain into something buildable, the group hired the Furst-Clark Dredging Company, which set about filling the uneven stretches that would become the Miramar subdivision. Spanning 35 bayfront acres, Miramar offered homesites priced from $1,750 to $8,000, with the choicest lots arranged in a sweeping semicircle along the waterfront. A sturdy 1,800-foot seawall, rising four feet above medium high tide, framed this arc, ensuring residents unobstructed views of Biscayne Bay. In a forward-looking touch rare for its time, the developers installed underground wiring for both electric and telephone service.

Miramar also boasted its own private dock, reserved for homeowners in the exclusive enclave. For years, the Miramar dock became far more than a place to board a boat, it evolved into a community landmark, hosting swim meets, canoe races, and boating events that repeatedly cast it as the starting or finishing point for life on the bay.

Incorporation on December 31, 1912

The northern suburbs were fast becoming some of the most desirable homesites in the Miami area, and with every new family that settled there, the shortcomings of life outside the city limits became more apparent. As the unincorporated community north of Miami swelled in population, residents found themselves lacking the basic services a proper municipality could provide. The push for self-governance finally gained momentum on Friday, November 29, 1912, when thirty of the district’s largest property owners gathered inside the Houser barn at 1604 NE Second Avenue (today’s address scheme). By the end of the meeting, they had unanimously agreed: it was time to incorporate North Miami as a city.

Preliminary arrangements for incorporation were made by a committee of five which included Mitchell D. Price, who was appointed chairman, John W. Graham, Edwin Nelson, E.P. Davis and R.C. Gardner. The committee was responsible for arranging for details of incorporation which took place on December 31, 1912, at 7:30pm in the Baptist Mission on the corner of Palm avenue and Flagler street (the names of these streets changed after the implementation of the Chaille plan in 1921). In an article published in the Miami Daily Metropolis on November 30th, the reason given for incorporation was the need of immediate improvements, such as water, sewerage, lights, streets, etc.

One of the committee members was quoted as saying:

“We are a part of Miami and belong to Miami and we intend to work for the future growth and prosperity of the community, both Miami and North Miami. That is why no one has suggested the idea of taking a distinctive name, but to have our city called ‘North Miami’ so it will appear on the maps as a part of Miami and the census rolls will include us in the census of Miami. We want to help make Miami a big city, but we also want necessary improvements, and to get these it appears best to incorporate as a separate city.”

The statement suggests that incorporation as an independent city may have been intended from the outset as a stepping-stone toward eventual annexation, a process that would unfold less than a year after North Miami was officially established. Although water lines had reached as far north as the City Cemetery and the county had paved Biscayne Drive (the future Biscayne Boulevard), much of the remaining street grid had been built by the original developers of the area’s various subdivisions. Those developers had little interest in carrying the long-term burden of maintaining the infrastructure they had put in place necessitating the incorporation of a formal municipality.

North Miami originally planned to extend from First Street, the northern boundary of Miami, on the south, the north line of the of Broadmoor addition on the north, and from the bay on the east to Prout Avenue (today’s NW 4th Avenue), on the west, which was equivalent to the western limit of the city of Miami. The boundaries included Hardieville and Overtown and as one committee member said: “but after we have once incorporated, Hardieville and colored town (as Overtown was referred to in 1912), will not be as they now are, for we will clean up those districts and make them respectable.”

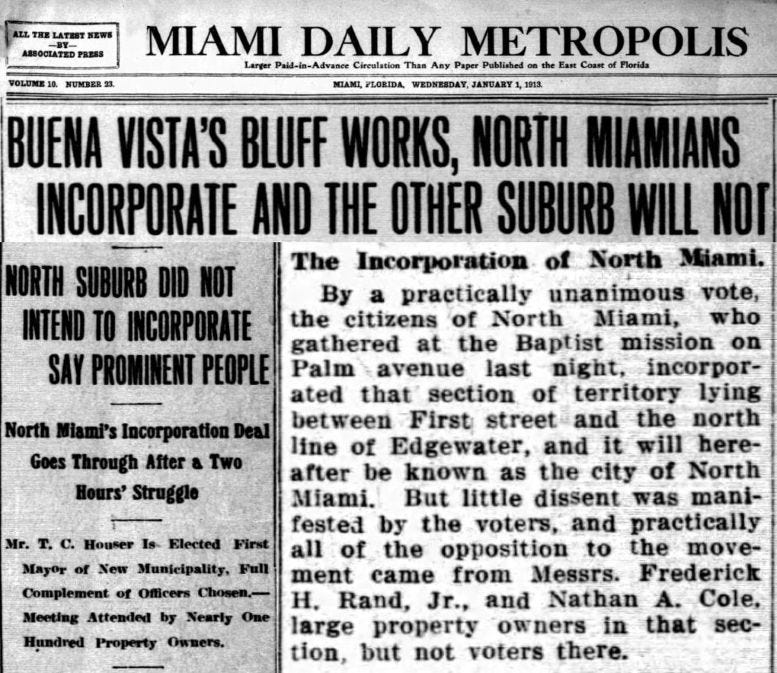

When the leaders of Buena Vista learned that North Miami intended to incorporate, they quickly announced plans to do the same. But with a later start, Buena Vista scheduled its incorporation vote for January 2, 1913, two days after North Miami’s planned date. The two communities soon found themselves at odds over their proposed boundaries, prompting negotiations that produced a workable compromise. Under the agreement, North Miami accepted a northern boundary at the north line of the Edgewater Addition (present-day NE 24th Street), which allowed Buena Vista to set its southern boundary farther south when it formally incorporated. At the time, the northern line of the Broadmoor subdivision marked the southern boundary of the unincorporated Buena Vista.

When the votes were tallied, the residents were nearly unanimous in voting for incorporation. The citizens of the new municipality voted Theodore G. Houser as their first mayor, Jesse Jay Combs was elected city clerk, and G.L. Chandler, Marshall. The five aldermen elected to serve on the city council were R.C. Gardner, John Graham, Edwin Nelson, M.T. Cann, and Frank Blanton Junior.

As for Buena Vista, the much-anticipated vote scheduled for January 2, 1913, never took place. Their leaders had never truly intended to incorporate. Instead, their announcement served as a strategic maneuver to prevent North Miami from pushing its northern boundary up to the southern edge of the Edgewater subdivision. The bluff worked, faced with the threat of legal action from Buena Vista’s leadership, North Miami accepted a compromise and adjusted its proposed northern boundary accordingly.

Annexation in 1913

Almost as soon as North Miami was born, discussions about joining the City of Miami began to surface. On January 21, 1913, a Miami delegation, led by Mayor John W. Watson, Henry Gould Ralston, and members of the Board of Trade, traveled north to meet with North Miami’s leaders. The gathering took place in the garage of Mayor Houser, where the new city’s council members and residents assembled to hear and debate the proposed terms of annexation.

In this meeting, as expressed by city clerk Jesse Jay Combs, the North Miami contingent wanted assurances of three things:

1) That an equitable proportion of the taxes paid by the property owners in North Miami shall be spent on improvements in North Miami.

2) That North Miami shall have just representation upon the council.

3) That the limits shall be extended from two and one half miles to three miles in all directions.

Combs stated:

“we are not trying to get out of paying taxes. That is not our objective at all. We simply want to have the improvements that we are entitled to from the taxes we do pay. Of course, we do not expect that every cent raised out here would be spent in this section, for we would want to pay our equitable share toward the support of the general government. But if a $200,000 bond issue is floated upon the city we want assurance that our proportion of that bond issue will come back to us in improvements in our own section of the city.”

Overall, the North Miami residents were willing to consider annexation if the improvements needed for their city could be delivered faster than if they operated on their own. The key to the negotiations centered on the amount needed for a bond issue to support the annexation and how the money raised would be allocated and invested in the new territories that would be annexed.

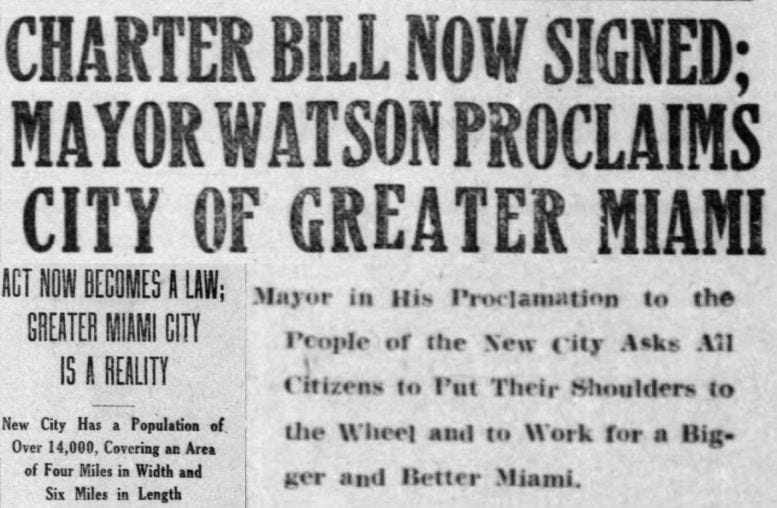

Negotiations continued through the winter of 1913, until the two municipalities came to an agreement prior to the Spring. On June 3, 1913, it was announced that Governor Park Trammell signed the Miami City Charter bill which authorized the City of Miami to annex North Miami and other territory adjacent to Miami’s original city boundaries.

Though North Miami existed as an independent city for barely six months, the residents of the annexed area finally achieved what they had sought since the idea of annexation first emerged in 1911. Essential infrastructure and public utilities were reliably provided by an established municipal government, bringing long-sought improvements to the community.

The Greater Miami charter, which formalized annexation of North Miami, also included the residential suburb of Buena Vista to the north, much of the Allapattah district to the west of Buena Vista, Highland Park, the General Lawrence Estate, Westmoreland, the golf links and the waterworks property to the west, and the southern parcels of the Southside (Brickell) neighborhood including the Bryan, Billingsly, Jennings and Deering (Vizcaya) estates. The new boundaries of the city would remain in effect until 1924, when the city would embark on another ambitious annexation initiative.

Epilogue

Although the leadership of North Miami had intended to clean up the red light district, which moved to a segregated northwest corner of today’s Overtown, it continued to operate with impunity. Also, despite Dade becoming a dry county in October 1913, the vice and crime continued for several years. In June 1917, a grand jury issued a disbandment order to officially end Hardieville eliminating the vice and crime that was so prevalent in the City of Miami’s northwest quarter.

While Edgewater began as a small subdivision platted by Frederic Rand and partners in 1912, after annexation it slowly became the reference for a large part of the neighborhood that was once North Miami. The Edgewater neighborhood now spans from roughly the Venetian to the Julia Tuttle causeways, or from NE 17th to NE 37th streets. This traverses the original southern boundary of the Miramar subdivision to the northern boundary of Broadmoor, both of which were developed by Rand.

As early as 1946, plans were taking shape to create a park near the Miramar subdivision. Those plans came to fruition in the early 1960s, when the Army Corps of Engineers dredged Biscayne Bay to deepen a navigation channel creating a need for a place to deposit the excess bay bottom. Part of the fill was used to form what became Margaret Pace Park in 1962, named for civic and preservation advocate Margaret Pace, founder of the Miami Garden Club. Through her tireless efforts, she became one of the leading voices for expanding Miami’s green spaces during the mid-twentieth century.

After annexation, the key leaders of North Miami continued to pursue their business and civic interests in the newly expanded City of Miami. Theodore G. Houser, since his arrival in 1904, was affiliated with some of Miami’s most important financial institutions. He served on the board of the First National Bank of Miami beginning in 1908 and was one of the founders of the Miami Savings Bank in 1915, which changed its name to First Trust and Savings Bank, and expanded its offering, in 1918.

Later, Houser went on to found and serve as president of the Florida Bond and Insurance Company, while also holding the role of vice president at the Houser Company, a family enterprise established in 1919. However, the pace and pressure of his many business commitments took a toll. Only a few years after settling in the Morningside neighborhood, Theodore Houser died by suicide in September 1928. His obituary suggested that his relentless work schedule and the strain of overseeing multiple ventures had contributed to a nervous breakdown.

North Miami’s city clerk, Jesse J. Combs, carried a strong sense of civic duty with him when he moved to Miami from Apopka in 1909. Though he had grown up in North Carolina, Combs enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War, driven by his opposition to slavery. After the war, he relocated his family to Apopka, Florida, where he served as a United States Commissioner. His commitment to public service continued there as he was elected mayor for five terms and served on the school board for multiple terms.

Since their sons had already settled in Miami, Jesse J. Combs Sr. and his wife often traveled to South Florida before ultimately relocating there themselves. After the move, Combs was appointed by Governor Gilchrist to serve as a probation officer, working with incarcerated juveniles. In 1912, he successfully ran for Justice of the Peace, a position he had also held in Apopka, and served several terms until 1919. Combs later returned to North Carolina, where he died on July 1, 1932, in Henderson after a long illness. He was 85 years old.

One of the greatest rewards of researching South Florida’s history has been uncovering my family’s connection to the places and events that helped shape the young City of Miami. Jesse J. Combs Sr., my great-great-grandfather, emerged in my research as a figure whose story I had never fully known until I delved into the history of North Miami. The deeper I explore Miami’s past, the more I recognize how this passion project has illuminated my family’s role in the city’s formative years, giving me a richer understanding of our place in the Magic City’s story.

Fantastic post. Thank you!

Regarding : "uncovering my family’s connection to the places and events that helped shape the young City of Miami. Jesse J. Combs Sr., my great-great-grandfather, emerged in my research as a figure whose story"

Yes! To me, this kind of personal connection really enhances my (and I'm sure others) interest in your historic documentation. I hope other readers will comment and share any family connections to these fascinating stories also. Personal touches give the history a kind of soul.