Segment of Berlin Wall in Downtown Miami

The story of how a piece of world history found its way on the downtown campus of Miami-Dade College in 2014.

Traveling north on NE Second Avenue toward NE Third Street, it’s hard to miss a graffiti-covered cement block that looks more at home in the artsy streets of Wynwood than along the promenade of Miami Dade College’s downtown campus. Standing 12 feet tall, 3 feet wide, and weighing four and a half tons, the exhibit is a powerful reminder of how fragile and hard-won freedom can be.

This massive slab was once part of the Berlin Wall, which divided East and West Germany from 1961 until 1990. Installed at the corner of NE Second Avenue and NE Third Street in 2014, it was a gift from Miami’s German Consulate General. Today, the segment serves as a permanent monument, urging passersby to remember a time when a wall split Berlin in two, built to keep East Berliners from escaping the Soviet-controlled German Democratic Republic, more commonly known as East Germany. This is the story of how a piece of that history found a permanent home at Miami Dade College.

Dividing of Germany After WWII

After World War II, Germany was defeated and occupied by the Allied powers. As part of the Potsdam Agreement, the country was divided into four zones of control with oversight of three of the zones by the United States, the United Kingdom and France, and the fourth zone controlled by the Soviet Union. The capital of the country, Berlin, was split the same way even though it was deep inside the Soviet zone.

Over time, political tensions between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union grew into what was labeled as the Cold War. The western zones merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), a democratic state aligned with the West, while the Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), a communist state under Soviet influence.

In the early years of this division, West Germany prospered under the Marshall Plan, which provided financial aid to rebuild Europe, while East Germany lagged in its recovery. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) was controlled by the Soviet-backed Socialist Unity Party (SED) and led by Walter Ulbricht, who fashioned his rule after Lenin and Stalin.

West Germany’s economic boom, fueled by the Marshall Plan, combined with growing political repression in East Germany, drove a wave of East Germans seeking a better life in the West. As the GDR tightened its borders across the eastern zone, Berlin became the main escape route for those desperate for greater freedom and opportunity.

During the first decade of socialist rule, Walter Ulbricht crushed an East German uprising in 1953, silenced dissent, and struggled with a mass exodus from East to West Germany. Nowhere was this migration crisis felt more acutely than in the divided capital, Berlin.

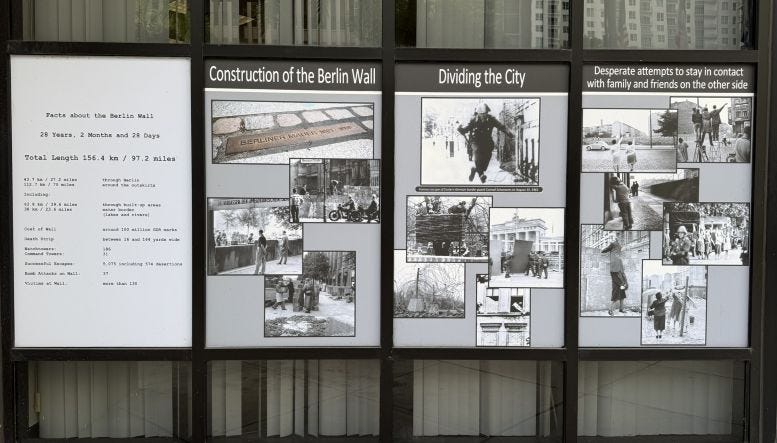

Construction of the Wall in 1961

As defections from East to West mounted by the early 1960s, Walter Ulbricht’s government sealed the border in Berlin and began constructing the Berlin Wall on August 13, 1961. Just days later, on August 22, Ida Siekmann became its first casualty when she fell to her death trying to leap from her apartment into West Berlin. Over the next 28 years, roughly 140 people died at the Wall, 91 of them shot by East German border guards under a “shoot-to-kill” order that was not rescinded until April 1989.

Once the Wall stood, life in East Germany settled into a controlled, modest lifestyle by Western standards. The socialist state guaranteed jobs, affordable housing, and healthcare, but at the cost of personal freedom and consumer choice. Many East Germans lived in drab, prefabricated apartment blocks and endured chronic shortages of basic goods, from fresh produce to household appliances. Though the economy provided stability, it lagged far behind West Germany, struggling to keep pace with its modern, market-driven counterpart.

While the state guaranteed necessities, it did so at the cost of personal freedom. The ruling Socialist Unity Party, supported by its secret police, the Stasi, kept tight political and social control, monitoring citizens and silencing dissent. After the Berlin Wall rose in 1961, travel to the West was almost entirely banned, and escape attempts carried deadly risks. Culture, education, and the media were shaped by socialist ideology, fostering a society that felt orderly and secure, yet constrained, watched, and cut off from much of the outside world.

In 1963, only two years after the Berlin Wall was built, President John F. Kennedy visited West Berlin and delivered one of his most memorable speeches at the height of the Cold War. From that moment until the Wall’s fall in 1989, every U.S. president after Kennedy traveled to West Berlin to speak, offering optimism that one day all men and women will be free of communist tyranny.

Ich bin Ein Berliner Speech in 1963

President John F. Kennedy’s “Ich bin Ein Berliner” speech, delivered in West Berlin on June 26, 1963, was a powerful statement of solidarity with the people of the city. Speaking at the height of the Cold War, Kennedy condemned communism and the Berlin Wall as symbols of oppression, while celebrating West Berlin as a beacon of freedom surrounded by tyranny. His declaration, “Ich bin Ein Berliner,” meaning “I am a Berliner,” was meant to assure Berliners that the United States and the free world stood firmly with them.

The speech also served as a broader message to the Soviet Union, emphasizing that the struggle between democracy and communism was a moral one, not merely political. By aligning himself symbolically with the citizens of Berlin, Kennedy reinforced America’s commitment to defending freedom in divided Europe and offered hope to those living under communist rule that their plight had not been forgotten.

Tear Down that Wall in 1987

On June 12, 1987, President Ronald Reagan visited West Berlin during the final years of the Cold War and delivered one of his most famous speeches. Standing before the Berlin Wall, he highlighted the stark contrast between the freedoms enjoyed in the West and the oppression faced by those living under Soviet control in the East. Reagan’s words underscored the Wall not merely as a physical barrier, but as a symbol of the division between liberty and authoritarianism.

The central moment of the speech came when Reagan directly addressed Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, urging him to “tear down this wall.” This appeal was both a moral and political challenge, calling on the Soviets to dismantle the symbol of oppression and allow East Germans the freedom to choose their own future. By framing the Wall as a global symbol of repression, Reagan reinforced the idea that the struggle for freedom extended beyond Berlin to all those living under communist regimes.

Beyond its immediate political message, the speech was meant to inspire the citizens of West Berlin and those trapped in the East. Reagan emphasized that the desire for liberty and human rights was universal, and he reminded the world that the United States stood firmly in support of those living under tyranny. The address combined diplomacy, moral conviction, and symbolic power, resonating both at home and abroad.

Ultimately, Reagan’s speech became a defining moment in the narrative of the Cold War. While it did not directly bring down the Wall, it reinforced the West’s commitment to freedom and human rights and placed public pressure on the Soviet Union. Today, it is remembered as a powerful call for unity, liberty, and the eventual end of Germany’s division.

Wall Removed in 1989-90

By the late 1980s, mounting pressure from widespread protests, economic struggles, and political reforms in Eastern Europe made the East German government increasingly unstable. Citizens demanded greater freedom of movement, and mass demonstrations in cities like Leipzig and East Berlin intensified, signaling that the regime could no longer control the population through force alone.

On November 9, 1989, a government spokesperson mistakenly announced that East Germans would be allowed to cross the border immediately. Thousands of Berliners surged to the checkpoints, overwhelming border guards who, unprepared and unsure how to respond, eventually opened the gates. Jubilant crowds climbed the Wall, chipping away at it with hammers and celebrating a moment that had seemed impossible just months before.

The fall of the Wall marked the symbolic end of the division between East and West Berlin and quickly became a powerful emblem of freedom and the collapse of communist control in Eastern Europe. Families and friends reunited after decades of separation, and scenes of celebration were broadcast around the world, capturing the joy and relief of millions.

In the months that followed, the Wall was systematically dismantled, and the border between East and West Germany was gradually reopened. Less than a year later, Germany was officially reunified on October 3, 1990, transforming the political, social, and cultural landscape of Europe and signaling the nearing end of the Cold War.

Segment of Wall on MDC Campus

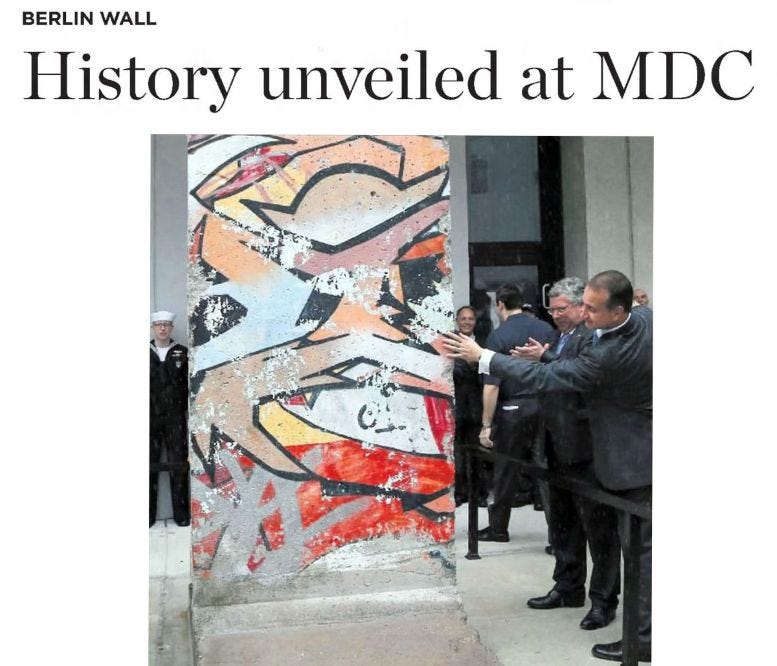

After the Berlin Wall was dismantled, segments of the structure were sold at auctions in Berlin and Monte Carlo and, over the following two decades, found their way to displays around the world. As the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Wall’s opening approached, Miami’s German Consul General, Juergon Borsch, proposed bringing a segment to the City of Miami to Mayor Tomas Regalado and Miami-Dade College President Eduardo Padrón, both of whom enthusiastically supported the idea.

Once a segment was secured, it was transported from Germany to Miami, arriving three weeks before the dedication ceremony. Weighing 10,000 pounds, the structure was stored until Sunday, November 9, 2014, marking the date of the unveiling and dedication ceremony of the historic artifact. Today, it stands as a permanent exhibition on Miami-Dade College’s main campus, at the northwest corner of NE Second Avenue and NE Third Street.

The dedication ceremony carried all the pomp and circumstance of a major public event, featuring speeches by local political leaders and the attendance of 1,500 people who braved afternoon storms to celebrate. Guests waved German flags, enjoyed bratwurst, and joined in honoring both the unveiling of the Wall segment and the 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall.

The German Consulate presented the segment as a permanent gift to Miami, expressing gratitude for the support the American people offered Germans in their struggle for freedom from communist rule. Today, the segment stands as a powerful reminder of the fragile line between oppression and liberty, as well as between scarcity and prosperity.