Vizcaya on Christmas Day in 1916

The story of the day that James Deering, Paul Chalfin, and guests celebrated the grand opening of Villa Vizcaya on December 25, 1916.

As the holiday season of 1916 drew near, James Deering, a recently retired executive of the agricultural machinery giant International Harvester, was growing increasingly frustrated with the slow progress of his ambitious Miami estate. Deering had purchased sixty acres of Brickell Hammock from Mary Brickell on December 31, 1912, fully expecting to take up residence in his grand Italian-style villa by November 1915. He would purchase additional acreage after the initial purchase allowing his estate to span a total of 180-acres.

That timetable soon proved unrealistic. Delays in the delivery of architectural drawings, shortages of building materials, the slow arrival of antiquities acquired overseas, and the formidable task of clearing and preparing the hammocked land all conspired to push completion back by more than a year. Compounding these challenges were the resource constraints brought on by the outbreak of World War I in Europe in July 1914. Although construction began in the fall of 1913, Villa Vizcaya would not be ready for permanent occupancy until December 1916. This is the story of James Deering’s long-awaited move into Vizcaya on Christmas Day, 1916.

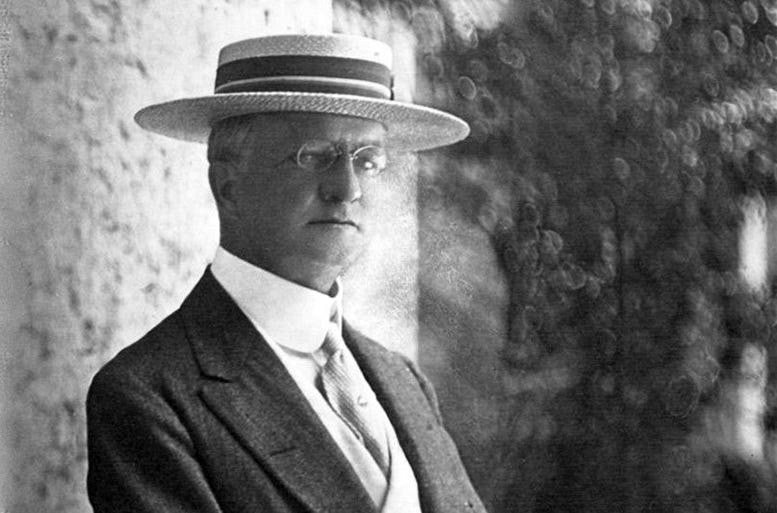

Owner of Villa Vizcaya

James Deering was born in 1859 into one of America’s most influential industrial families. He was the son of Clara and William Deering, founder of the Deering Harvester Company, which later merged with several competitors to form International Harvester in 1902. Educated at Harvard University, Deering entered the family business in the 1880s and rose steadily through its executive ranks. By the early twentieth century, he had become vice president and a key figure in the management of International Harvester, helping guide the company during a period of rapid expansion that made it one of the world’s largest manufacturers of agricultural machinery.

Despite his success, James was known as a reserved and private man who preferred travel, art collecting, and intellectual pursuits to public corporate life. Chronic health issues increasingly influenced his decisions, and in 1909 he retired from active management at International Harvester at the age of fifty. Financially independent and free from corporate responsibilities, Deering spent the following years traveling extensively in Europe and the Mediterranean, developing a deep appreciation for classical architecture, landscape design, and antiquities.

These experiences, combined with his desire for a winter residence conducive to his health, ultimately led him to South Florida. In 1912, he purchased acreage along Biscayne Bay from Mary Brickell, setting the stage for the creation of Villa Vizcaya, an estate that was beyond the imaginations of the many wealthy transplants who constructed their grand winter estates in Miami during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Visionary of Deering’s Palace

Paul Chalfin was a Harvard-educated artist and designer whose aesthetic vision played a central role in shaping Villa Vizcaya. Trained in painting and art history, Chalfin studied at Harvard and later in Europe, where he developed a deep appreciation for classical, Renaissance, and Baroque art and architecture. Although he was not a formally trained architect, Chalfin possessed an extensive knowledge of European decorative arts and a strong instinct for theatrical composition and historical reference, qualities that made him uniquely suited to James Deering’s ambitions for Vizcaya.

Chalfin was recommended by celebrated Elsie de Wolfe, the New York and Paris decorator, as well as Mrs. Jack Gardner, to James Deering in 1910, and the two formed a close professional and personal partnership. Deering appointed Chalfin as artistic director of the Vizcaya project, entrusting him with the overall aesthetic conception of the estate. Working closely with architect F. Burrall Hoffman Jr. and landscape designer Diego Suarez, Chalfin oversaw the design of interiors, gardens, and decorative programs, drawing inspiration from Italian villas, French gardens, and old world Spanish and Mediterranean influences. He traveled extensively on Deering’s behalf to Europe, acquiring antiquities, architectural fragments, furnishings, and artworks that gave Vizcaya its layered sense of age and authenticity.

The relationship between Chalfin and Deering was one of mutual dependence and occasional tension. Deering relied heavily on Chalfin’s artistic judgment and granted him remarkable creative freedom, while Chalfin depended on Deering’s patronage and trust to realize his grand vision. Their collaboration resulted in one of the most ambitious and imaginative estate projects of early twentieth-century America.

Chalfin was a forceful personality with unwavering conviction in his artistic vision, a combination that made his role both confrontational and, at times, controversial. Yet he remained steadfastly committed to that vision, attending to every detail, including the carefully orchestrated unveiling of Deering’s estate, until it was formally turned over to the man who had entrusted him with creating a residence both singular in character and destined to become one of South Florida’s most iconic landmarks.

Holiday Season of 1916

Already disappointed that his Miami estate would not be completed by November 1915, James Deering grew even more frustrated in August 1916 when he learned that only sixty-eight percent of the work on his residence had been finished. Unhappy and restless, Deering chose to remove himself from the situation, traveling to Paris, France, to stay at a residence he had purchased earlier in the summer.

Deering remained in Paris longer than he had originally planned, returning to the United States and arriving in New York on November 23, 1916. From there, he telegraphed Paul Chalfin to ask whether his Miami home would be ready to receive guests by December 15. The guests, consisting of relatives and close friends, did not require the house to be fully furnished. Deering was not expecting “an ashtray on every table and a picture on every wall,” as noted by Kathryn Chapman Hardwick in The Lives of Vizcaya: Annals of a Great House. Two days later, Deering sent another telegram informing Chalfin that he was dispatching his butler, Baylis, to be followed by the rest of the household staff. Deering and his guests planned to arrive on or prior to December 20.

A December 17 headline in the Miami Herald announced, “James Deering Arrives Home.” He arrived by train at 11:30 p.m. and spent the night at the Hotel Halcyon. According to the article, Deering planned to inspect his residence the following day, as the men employed on the estate had been working day and night to prepare for his long-anticipated arrival.

The article described how Deering would find the property when he arrived:

“The grounds now present a most pleasing appearance, and the millionaire harvester king will, no doubt, be agreeably surprised when he visits his magnificent five million dollar estate today.”

A second article in the Miami Herald, published on December 22nd shared that Mr. James Deering hosted a dinner party at his estate on Wednesday, December 20th. The article shared the following details:

“The first dinner party given by Mr. James Deering at his newly completed estate, and the first since the occupancy, several days ago, was given by him on Wednesday evening. Dinner was served in the Chinese breakfast room. Mr. Deering’s guests were Mr. and Mrs. B.O. Winson, Mr. Paul Chalfin and Mr. Louis Koons. To celebrate the event huge bonfires blazed from all the islands before the lagoon and the house was illuminated. Mr. Deering’s other guests will arrive on Sunday to complete his party for Christmas.”

Although both articles suggest that James Deering took up residence before December 25, 1916, it was the Christmas evening celebration that marked the official grand opening of Vizcaya and Deering’s formal move into his new grand estate.

Grand Opening on Christmas Day

Paul Chalfin, described by Kathryn Chapman Harwood as a “past master of pageantry” who was “determined to wring the last ounce of high drama out of the spectacular opening of Villa Vizcaya”, intended the Christmas evening celebration to serve as the public debut of his masterpiece. To heighten the theatrical effect, Chalfin required guests to arrive in “Italian gypsy costume,” transforming the occasion into an Italian masquerade that echoed the Renaissance essence of Deering’s villa.

Although James Deering was the guest of honor, he played no role in planning the event and was temperamentally ill-suited to its extravagant display. Reserved by nature, Deering was instead guided through the evening as Chalfin saw fit, a central figure in a carefully choreographed spectacle. As darkness settled over Biscayne Bay, Deering made his dramatic arrival by his yacht, the Nepenthe, completing Chalfin’s meticulously staged vision for the opening of Vizcaya.

The American Weekly Magazine, in a Sunday feature story published thirty-five years later, described the arrival of James Deering on Christmas night of 1916 to take possession of Vizcaya:

“A whistle shrilled. A light flashed on. All activity ceased and silence descended on the great estate. The rooms of the huge palace lighted up one by one. In the terraced gardens, scores of Japanese lanterns began to play a symphony of colors. On each side of the marble stairway leading to the main door of the palace, servants in gold-faced uniform affected by European armies of the eighteenth century approached ancient cannons, lighted fuses in their hands. Again, the whistle sounded and the two cannoneers, acting as one, applied fuses to the touchholes and the canons boomed in unison as the yacht’s gangplank went down, and onto the landing stage stepped, not a king in royal raiment, but a little man in a high silk hat and a high stiff color.”

Following the grand entrance, an elaborate celebration unfolded throughout the house. As guests wandered from room to room, they were accompanied by strolling musicians, while a corps of butlers moved seamlessly among them, offering refreshments from silver trays. The gathering included Deering family members and prominent neighbors, among them Mr. and Mrs. William Jennings Bryan, William Matheson, and many other notable figures from Miami society of the era.

Villa Vizcaya – Post Grand Opening

After James Deering officially took up residence at Villa Vizcaya, work on the estate continued. While the interiors required only minor finishing touches, substantial work remained in the gardens, where the ambitious landscaping plans would not be fully realized until the early 1920s. By 1922, the grounds were largely complete, allowing Deering to enjoy the estate as he had originally envisioned it.

His enjoyment, however, was brief. On September 21, 1925, James Deering died at sea while returning to the United States aboard the SS Paris, succumbing to complications from pernicious anemia. Having no children, Deering left his estate, including Villa Vizcaya, under the guardianship of his nieces, Marion Deering McCormick and Barbara Deering Danielson.

The financial burden of maintaining Vizcaya ultimately proved overwhelming. In 1952, Marion and Barbara sold the estate to Dade County and donated its art, furnishings, and sculptures as part of the sale. Following extensive restoration, the property was converted into a public museum. Today, Villa Vizcaya operates under the stewardship of the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Trust, a nonprofit organization, through an agreement with Miami-Dade County. Since opening to the public on March 11, 1953, this Gilded Age–era Italian palace has been enjoyed by generations of residents and visitors, its halls and gardens brought back to life through tours, student visits, weddings, and special events.

Resources:

Book: “The Lives of Vizcaya – Annals of a Great House”, by Kathryn Chapman Harwood (Copyright 1985)

Miami Herald: “Realty Stunt of $180,000 Pulled Off”, on January 1, 1913.

Miami Herald: “James Deering Arrives Home”, on December 17, 1916.

Miami Metropolis: “The Story of the House that James Deering Built”, on December 21, 1916.

Miami Herald: “First Dinner in New Home”, on December 22, 1916.