Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1899

The young City of Miami, having only incorporated in 1896, was faced with a city-wide epidemic in 1899. The entire city was quarantined on October 22, 1899 and was in effect until January 15, 1900.

It is hard to imagine that a simple mosquito bite could lead to an epidemic that would quarantine an entire city for several months. If you live in South Florida, it is nearly impossible to avoid being bitten by the pesky flying insect at some point during the year. In the fall of 1899, the three-year old City of Miami was panicked and then quarantined for nearly three months because of a virus transmitted by the mosquito. However, it wouldn’t be until the end of 1900 that medical professionals learned how the yellow fever virus was really transmitted.

During the roughly three-month duration of the outbreak, there were plenty of misunderstandings about how the virus was spread. The reaction to the plague included isolating infected patients and burning their possessions to ensure the contagion was contained. However, this epidemic seemed like it could destroy the idea of the Magic City before it really got going. It was during these uncertain times that Miami’s pioneers ensured that the city would be defined by resiliency and not fear.

Yellow Fever in Region

While a yellow fever outbreak was a concern every two years in Florida during the nineteenth century, it was almost a year-round health concern in Cuba. There were consistently several cases at any given time in Havana. As February of 1899 approached, Dr. James Jackson, Health Officer of the Port of Miami among his many other responsibilities, declared that all equipment and baggage coming from Cuba be fumigated. A month later, on March 31, he escalated his precaution and issued a formal quarantine against passengers and goods arriving from Havana.

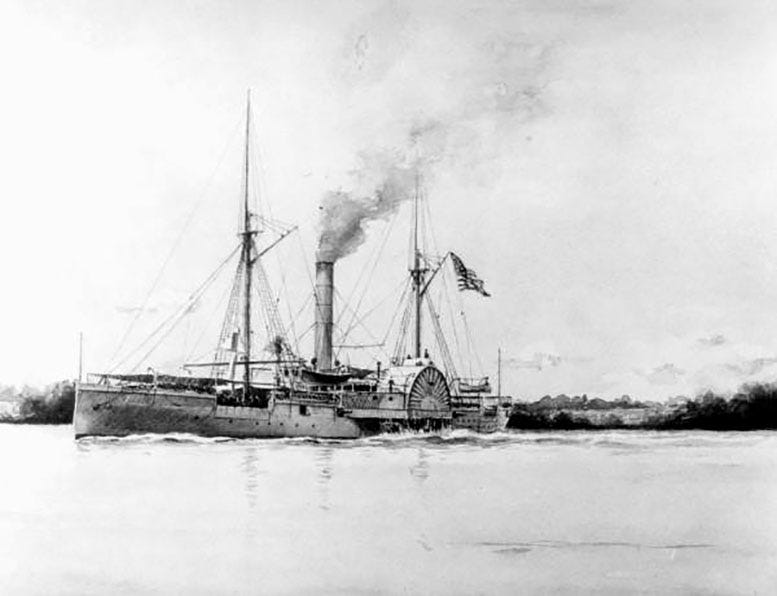

The wooden hull ‘Lincoln’ was replaced with the steel-hull steamer ‘Miami’ as the vessel that transported people and equipment from Havana. It was believed that yellow fever contagion was more likely held and spread from wood than it was from steel.

Dr. Jackson’s precautions were with merit when he was made aware on August 11 that a soldier from Hampton, Virginia, who had just returned from Havana, contracted yellow fever. A few days later, Jackson was notified that a case of yellow fever was found in Key West. These two cases prompted the doctor to institute a quarantine against visitors from Key West effective September 1, 1899.

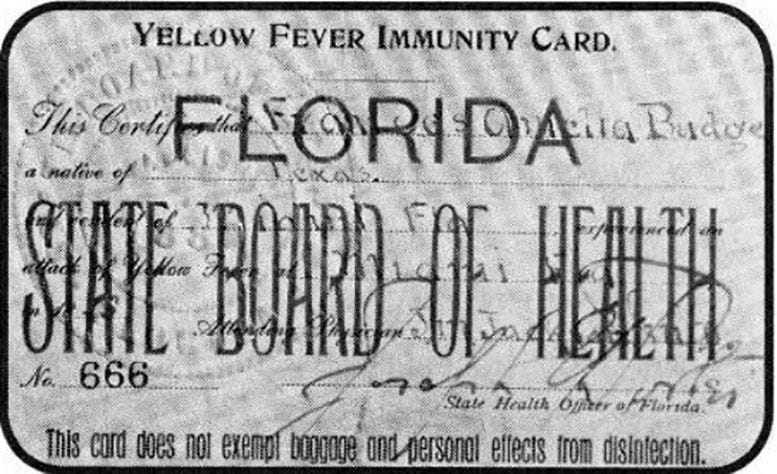

The next day, September 2, the steamer Santa Lucia, carrying fumigation equipment, positioned itself and anchored at the mouth of the channel to Cape Florida. Anyone from Key West intending to do business in Miami had to do so from the steamer. Orders were taken by people referred to as “immunes” and were fulfilled by the same party. Immunes were anyone who could prove that they had been exposed to yellow fever in the past. It was widely believed that if you survived an exposure to yellow fever once, you were immune from contracting it a second time. “Immunes” were issued a “Yellow Fever Immune” card indicating their health profile as it pertained to the contagion.

First Case in Miami

It was the day before the quarantine order that the Steamship ‘City of Key West’ arrived and disembarked two passengers. Dr. Jackson was able to track down both passengers and found one, Samuel Anderson, in bed with a fever. The doctor diagnosed Anderson with yellow fever and immediately quarantined the home. No one could leave or come into the house. There were two “immunes” stationed as guards to ensure the quarantine was honored. Jackson wired Dr. J. Louis Horsey immediately to get a second opinion. He had extensive experience diagnosing and treating yellow fever.

On September 4, Dr. Horsey arrived into Miami and confirmed Dr. Jackson’s diagnosis of Samuel Anderson. The entire Anderson family was put aboard a small schooner and sent to Bear Cut for an eighteen-day quarantine. In the meantime, “the house was fumigated, the yard cleaned, and the ground was wetted with bichloride of mercury solution and coated with lime” according to Jackson and Horsey’s official report. Also, as was customary with yellow fever during this era, the bed and bedding were destroyed by fire to ensure the virus had been eliminated.

Employee of Hotel Miami was First Official Case

In 1899, it was believed that yellow fever was spread by contact with others who were inflicted with the contagion. In order to avoid being exposed to the virus, some Miami residents decided to leave town and others decided to get away from the crowd by pitching a tent in the woods outside the city limits. They would spend the night in the woods and return to the city only to conduct business. John Seybold was one resident who chose to retreat to the woods during this time.

On September 19, another Miami resident was struck with the disease. I.R. Hargrove, a dance instructor at the Hotel Miami became sick after spending the night on a cattle boat named ‘Laura’, which was moored at a dock at the end of Avenue D (Miami Avenue), at the foot of the Miami River.

As soon as he became symptomatic, he was brought to the second floor of Hotel Miami and was seen by Dr. Jackson and Dr. Horsey. Although he was tended to by friends around the clock, he ended up passing away from the illness on September 26. Shortly after his death, the hotel was quarantined and all those who came into contact were sent out to the Santa Lucia for at least two weeks. The hotel was closed air tight and completely disinfected during the quarantine period.

City of Miami was Quarantined

As September ended and October began, city officials were beginning to think that the epidemic was nearing its end. However, there were mild cases of the fever from a couple of other passengers on ‘Laura’. One of those passengers, James Flye, died of what was originally believed to be renal failure. An autopsy was done in the middle of the night by Dr. Horsey and he concluded that Flye died from yellow fever. Although there were other doctors in town who disagreed, the final decision was in alignment with Horsey’s conclusion.

Five days after returning from quarantine on the Santa Lucia, Hotel Miami clerk, Philip DeHoff, became sick on October 17. He was one of the employees who spent time tending to Hargrove after he became sick. DeHoff ultimately broke his fever and recovered from the illness.

Given the handful of cases that were being reported in Miami, Dr. Robert Drake Murray of the United States Marine Hospital Service, a respected authority on yellow fever, arrived in Miami and declared seven active cases. Based on the number of cases, the Florida State Health Officer, Dr. Joseph Yates Porter, had no choice but to place the entire City of Miami under quarantine.

During the official quarantine notice, Hargrove was considered the first case of yellow fever in town. Since Samuel Anderson was isolated quickly and there wasn’t a second case for another three weeks, his illness, and subsequent death, was not considered a part of the epidemic period.

The quarantine was taken very seriously. So much that all outgoing mail was fumigated before it left the city. There were guards placed at the city limits in all directions to make sure that no one could enter or leave the quarantine area. Family members who left town prior to the quarantine were not re-united with their family or home until it was officially lifted.

Peak of the Epidemic

By late October, there were so many new cases of yellow fever that J.K. Dorn, while traveling around town with Dr. Jackson, would gather and post names of the new cases, as well as death notices, each day on a board located outside of Townley Brothers Drug Store. The death toll from the epidemic was peaking during this period. Edwin Nelson, who sold coffins as well as furniture, rode along with “White Horse Douglas”, who owned and drove a horse-drawn “hearse” to transport the deceased.

The epidemic was impacting families. There were children separated from parents to isolate and keep the disease from spreading. An organization called the Miami Relief Association opened a home to house and care for the displaced dependents until their parents were well enough to reunite with their children.

On October 27, Camp Francis P. Fleming was a detention center established on the bay near today’s Rickenbacker Causeway. It consisted of several water vessels including the Santa Lucia. Dr. Horsey oversaw the camp. Anyone exposed to yellow fever was detained for ten days. If they showed no symptoms after ten days, they were taken by boat to Lemon City, beyond the quarantine line, and “were free to leave to points north, not south.” If they showed signs of yellow fever, they were taken back to Miami for treatment.

Camp Fleming closed on November 6, at which time, Camp William E. McAdam, a land-based detention camp opened at Fulford, which is near today’s NE 163rd Street and Biscayne Boulevard. The camp was situated in the middle of Judge P.W. White’s orange grove. It consisted of tents organized in rows for the detainees. It could accommodate over one hundred internees and was fully integrated with black and white residents.

Camp Fleming consisted of three sections: one for those with no symptoms, a second for those who were symptomatic and the third for patients that needed medical care. When someone was diagnosed with yellow fever, they were transported to the third section. Only three victims were diagnosed as having the virus during the camp’s brief existence. The camp closed on December 2, 1899.

Emergency Hospital Built

Miami’s City Hospital was completed on September 22, 1899 and was located at Third Street and The Boulevard (today’s NE Ninth Street and Biscayne Boulevard). It was located directly across the street from the southern edge of today’s Museum Park. However, for some reason and despite opening at the beginning of the epidemic, the hospital did not treat any yellow fever patients during the outbreak.

W.W. Prout, a contractor and secretary of the Miami Relief Association, decided to take matters into his own hands. He agreed to finance an emergency hospital and broke ground on Sunday, October 27th, for a single-story facility which was built along NE First Avenue (Avenue C), between NE Third and NE Fourth Streets. The building was eighteen by eighty-eight feet and consisted of a large open area, an office, baths, completely equipped with triage hospital equipment. There was a wing with a kitchen and an area to prepare food. It took four days to construct the temporary hospital and it was ready to accept patients by October 31st.

Henry Flagler paid the salaries and travel costs for immune nurses who were brought down from Jacksonville. He also reimbursed Prout for the money he laid out to build the hospital. Dr. Porter was the lead physician and was put in charge of the emergency hospital. He was joined by four volunteer doctors who also provided care for the yellow fever victims.

After the epidemic ended in January of 1900, the emergency hospital closed as a medical facility. According to an advertisement in the Miami Metropolis on December 7, 1900, the building for the temporary hospital was listed for sale.

Fire in Hotel Miami

After the Hotel Miami was fumigated following Hargrove’s death on September 20, one of its three floors was used as a temporary hospital. On November 12, a fire broke out in one of the rooms which rendered the wood-structured building unsalvageable. At the time of the fire, there were five patients located on the floor that operated as a makeshift infirmary, and everyone was able to exit the burning structure safely. However, one of Miami’s first hotels was consumed by flames in less than thirty minutes. The fire also destroyed five buildings around the hotel.

Early speculation was that the fire was set deliberately to rid the city of the yellow plague. However, it was determined that the fire began in a room of one of the patients when an attendant accidently knocked over a “blue flame oil stove”. Regardless of the cause, Julia Tuttle’s legacy hotel was gone a little more than year following her death on September 14, 1898.

Lifting of the Quarantine

The quarantine was officially lifted on January 15, 1900. The epidemic’s end marked a new beginning for the young City of Miami. Families came streaming back into the city. The Royal Palm Hotel opened for its fourth season and experienced a tourist season as if nothing had happened. There was a feeling of relief and a sense of hope that the Magic City had overcome adversity and its citizens could feel good about future prospects as they transitioned into a new century. However, for many residents, this epidemic was not easily forgotten.

The Yellow Fever epidemic of 1899 officially began in Miami on October 17, 1899 and ended when the quarantine was lifted. During this time, there were 220 cases reported which represented thirteen percent of the city’s population. Of the total cases reported, there were fourteen deaths attributed to the outbreak.

During this epidemic, medical professionals believed that the illness was transferred when a healthy person came into contact with someone infected with the virus. However, on October 27, 1900, the Reed Commission announced that it was the mosquito that acted as the transfer agent for the “parasite of yellow fever”. An insect bite was all it took for a healthy human to become ill with yellow fever. It was an insight that was put to good use in preparing the city to control any future outbreaks of yellow fever.

Resources:

Tequesta 1995: “Yellow Fever at Miami: the Epidemic of 1899” by William M Straight, MD.

The Philadelphia Medical Journal: “The Etiology of Yellow Fever” by Walter Reed, James Carroll, Aristides Agramonte and Jesse W. Lazear, October 27, 1900.

Miami News: “Yellow fever epidemic gripped city” by Howard Kleinberg on June 7, 1987.

Images:

Cover: Santa Lucia Steamer in 1899. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 1: USS Miami in 1899. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 2: Yellow Fever Immunity Card. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 3: Hotel Miami in 1897. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 4: Twelfth (Flagler) Street in 1899. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 5: Twelfth (Flagler) Street in 1899. Courtesy of Florida Memory.